Prince Caspian: Forward to the Past (or, Learning How to Enjoy a Sequel)

May 23rd, 2015 | Skip to comments

I have never met any dedicated reader of the Chronicles of Narnia who told me that Prince Caspian was her favorite volume.

I think I know the reasons why this might be so, and in due course, I will eventually get around to addressing this question. But let’s start here: sequels get no respect!

That said, let me unabashedly point out what every avid reader of C S Lewis knows: that Jack is as capable of creating a memorable theme or voicing a quotable line in Prince Caspian as he is in any of his works. And has, indeed, done so.

The trouble is that there are so many of them in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe! Nearly any follow up tale would have been, forgive the pun, dwarfed by its rich body of resonant dialogues and spectacular events. In a word, Prince Caspian is literally anti-climactic. But look at what it is up against:

First, in LWW, there is Professor Kirke’s wonderfully mysterious house with the magic wardrobe that Lucy the youngest finds first, and his eloquent rebuke of Peter and Susan for missing the clues that would have spared them worry over Lucy’s behavior: “Logic! . . . . Why don’t they teach logic at these schools!” Next, there is Mr. Beaver’s subtle but firm declaration of Aslan’s true character when Susan asks, “Then he isn’t safe?” And Mr. Beaver intones, “Safe? . . . Who said anything about safe? ‘Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.” Then there is the plaintive scene at the Stone Table, where Susan and Lucy keep their solemn vigil and the mice patiently nibble and gnaw to release Aslan from his bonds. Finally there is the coronation scene at the end, when the risen Aslan, triumphant over the White Witch through the deeper magic from before the dawn of time, slips away, and Mr. Beaver, ever the spokesbeaver for sober reality, explains, “He’ll be coming and going. . . . One day you’ll see him and another you won’t. He doesn’t like being tied down. . . . He’s wild, you know. Not like a tame lion.”

So this we can agree upon: Prince Caspian had no easy act to follow! Yet, It must be underscored that Lewis embued the tale with its own suspenseful plot devices, a grand share of memorable conversations all nestled within more than enough swashbuckling, court intrigue, species-bigotry and species-envy, not to mention fratricide, conniving advisors, and a new set of talking animal and mythological characters of the kinds that he dearly loved!

The trouble is, at the end of the day, it’s still a sequel, the follow-up to a beloved book, a planned sequel in the Narnian series by both publication date and story line. And Lewis signaled this by giving it the Narnian tales’ only subtitle, “the Return to Narnia.”

The key to enjoying and appreciating Prince Caspian is recognizing that its magic lies in returning to Narnia not a moment too soon. We all want to return to Narnia, but what if when we get there, Mr. Tumnus is gone, the Beavers have gone on to their reward, Cair Paravel is in ruins, and Aslan is missing. Missing? Ah, the plot thickens. “Nothing ever happens the same way twice.”

We learn that Timing is everything, Aslan’s Timing! Here is a story within a story, a tale of not only how one gets back to Narnia, but how one may have to leave it for good; and while the Pevensie children must relearn some hard won lessons about friendship and courage, Aslan also must “return” to teach and recover for all Narnians the precious gifts of freedom, honor, and loyalty.

Origin of the Tales

Before we say more about this, let’s put all of the Narnian stories in a larger context. First, I adjure all readers to read them in the order in which Lewis wrote and published them! For dramatic, thematic, as well as suspense purposes, it is crucial that LWW be the first to be read, followed by the Caspian Triad, then The Horse and His Boy (a kind of found tale, deliberately anachronistic), then Narnia’s origin story, The Magician’s Nephew, and, finally, the truly consummating The Last Battle. This is the most compelling and satisfying way to begin and complete a journey to Narnia.

When one says Lewis began to write these tales in the late 1940s, we are telling a partial untruth, for as he tells us in a couple of rich essays about writing for children and the reasons he created Narnia, he had carried around images of them in his head as young as sixteen, when he first envisioned a faun walking in a snow woods carrying some parcels and an umbrella, the faun who was to become Mr. Tumnus.

Lewis’s own imaginative childhood was rocked with the illness and eventual death of his mother when he was 9, and he spent the greater part of his early and post-adolescence in an intellectual retreat that blocked out the pain of his sorrow and his alienation from his equally distraught father. His mind roamed from mythology to philosophy to his own creative worlds as he lived in his forced isolation from brother Warnie, his imaginative playmate and fellow dreamer, amidst the boarding schools to which he was sent by his despairing father. (This is a period Lewis refers to as “Concentration Camp” in his memoir, Surprised by Joy.)

It was during this pre-Oxford, pre-war period that Lewis’ imagination was unshackled to explore further the world’s canon of stories, expand his sense of grand purpose in the universe, and exhale some of its dross. Much of what he would later create from inside a redeemed, Christian worldview, was in development even in this time of doubt. He never let go of the elusive pieces of Narnian mythology and landscape lodging in his heart and soul; he just had to wait for the right time to bring them to the forefront. Aslan was on the move, even then.

Throughout the mid-1930s to the end of the 1940s, Lewis built a remarkable, multi-faceted career as a literary critic and historian at Oxford University, a religious broadcaster on the BBC during WWI, a formidable writer of science-fiction and fantasy as ground-breaking as Arthur C. Clarke or H. G. Wells, and as a revered and preferred lay theologian, educating Christians on both sides of the Atlantic on the nature of the Christian faith in the modern world, and why it was credible, exciting, and intellectually respectable to believe in God and trust the Bible as a source of insight, despite its ancient origins.

As astounding as these achievements were, no one could have expected him to have become, by age 52, and as an unmarried bachelor, a world-renown, medal-winning writer of children’s books–volumes that have enthralled readers of all ages now for nearly 60 years. When Lewis decided, as he put it, to “see if we could make a story” out of the multiple, childhood-based “images in his head,” Aslan came bounding into his dreams, and “pulled all the stories together.”

Aslan is indeed the creator-King of Narnia, and of all the Narnian stories, LWW is clearly the most read and best known, for it introduces not only the four Pevensie children, but also Narnia’s most compelling character, the King of Man and Beasts, Aslan, the son of the Great Emperor Beyond the Sea. But that great imagination did not suddenly run dry when Lewis dreamed again, this time, not of roaring lions, but raging rodents, a band of mighty sword-wielding, chivalrous mice!

The Merits of Prince Caspian

If Prince Caspian is no LWW, there is no shame in that. For how could any story measure up to what is, in fact, a retelling of the greatest story ever told, the story with the greatest significance for every creature great or small, the scintillating and enchanting tale that delivers the “the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.”

(The Gospels themselves have their own sequels, the history, the letters, the apocalypse, all with valuable, essential information and authoritative life counsel—but the stories they tell, the doctrines they teach, ultimately pale in comparison to The Story, the narrative of the incarnation, the sinless life, the death and descent into Hades, and the triumphant resurrection and ascension of the Son of God. Only our dear physician and documentarian realist, Luke, knows the daunting task of writing a sequel to such momentous and monumental Good News!)

Having said that, I will tell you that there remains a most important lesson to be emphasized from the very start of this underrated and undervalued Narnian tale, namely, that in imagining and creating Prince Caspian, Lewis has taught us the profound but overlooked truth that life does have sequels. Life is, in fact, filled with sequels, that emphasize our heretofores, once-agains, and ever-afters.

There is an “ever after,” even after the seemingly “most important things” have already happened. How could anything that occurs after the death, resurrection, and triumph of Aslan to set things aright be anything but trivial. Aha! The recent slogan, “been there, done that,” the older slogan, “the show must go on,” and the oldest one of all, no doubt uttered by Adam and Eve more than once in the Garden, “life goes on,” is certainly just as true in Narnia. The question is not “how has life gone,” but how can life go on?

After our most momentous human experiences, our births, our graduations, our athletic competitions, our marriages, our deaths: life does go on. Prince Caspian lays before us not only an engrossing tale of betrayal and seduction, but spiritual wisdom about, and practical strategies for, handling the mundane, the obvious, the monotonous, and the ordinary–all the while pointing to the extraordinary adventures that lay still ahead on both sides of eternity.

The Boy Who Would Be King

Mentoring in valor, justice, and righteous rule is thematically the center of Prince Caspian. On our second look, a return excursion, the place we thought we knew well has dramatically changed; some things may look differently, but remain just as we left them—or do they? What will be our landmarks and anchors in the midst of confusion and turmoil if the Narnia we left is not the Narnia we now encounter?

While only a year of earthly time has passed for the Pevensies since their last visit to their kingdom, in their absence, Narnia has aged more than a thousand years; the memories of High Kings and Queens, and Aslan himself, have faded, and the native Narnians once again find themselves in need of redemption and a rightful ruler to be restored to the throne.

Narnian society, put aright by Aslan’s earlier sacrifice and resurrection, seems to have developed a social and historical amnesia. A dark age has set in. How could this be? What has gone wrong? Painful and debilitating questions have arisen and arrested development has beset their world: What should one believe? Why should anyone believe the “old stories”? Does Aslan even exist?

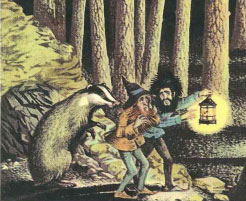

For Caspian, the once and future king, these are indeed not trifling issues; and when we first meet him he is but a callow youth in search of his true identity—charged with a simple mission to avenge his father’s death and arise to the kingly role for which he is destined. Like the many young kings depicted in the Bible and in many other world cultural narratives, he is in some ways wise beyond his years, yet his greatest trait is his humility. To find and embrace his true heritage, he must hold fast to the truths that his loyal counselor and guide, Doctor Cornelius, has preserved and faithfully relayed to him.

“Listen,” said the Doctor. “All you have heard about Old Narnia is true. It is not the land of Men. It is the country of Aslan, the country of the Waking Trees and Visible Naiads, of Fauns and Satyrs, of Dwarfs and Giants, of the gods and the Centaurs, of Talking Beasts.”

Though these sound like fairy tales, Dr. Cornelius assures Caspian they are true. Narnia was once filled with such amazing creatures and “miracles.” He must therefore surround himself with trustworthy, like-minded kinsfolk who also believe— creatures like the fearless Trumpkin, the dwarf who leads the newly returned Pevensie clan to him, and, of course, Reepicheep, the valiant mouse, whose tail becomes a tale in itself during the climax of the story. Likewise, Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy must sort out on little notice why and how they have suddenly been brought back to Narnia—and, upon understanding their mission and whom to trust, how they can gain the confidence of those agnostics with whom they must make common cause and entrust Narnia’s future?

We learn in Prince Caspian that vantage point is crucial—and one is responsible for both what and how one sees. On their second trip to Narnia, Peter and company find a Narnia in disarray—their once splendid castle in ruin, their would-be friends discouraged, and the citizens unaware or outwardly doubtful that there had ever been a golden age in which Narnia prospered under Aslan’s wise rule. Their new quest—to restore the rightful King to his throne and his subjects to faith in Aslan—is one that requires new resolve and not least a good memory for what Aslan had already taught them.

They must piece together the facts of their predicament and must help Caspian convince and lead his subjects in recovering their national identity and corporate faith as Narnians. In other words, the locals have no more reason to believe them than they do “the old stories.” They must by their courage and valor prove themselves again. Why should any self-respecting Narnian trust a Son of Adam or Daughter of Eve?

It is interesting thus to note the difference in temperament between these Sons of Adam and Daughters of Eve, who once came as seemingly uninvited guests into Aslan’s world, and those who belong to Narnia, whose birthright is peaceful living in the light of Cair Paravel. The Pevensie clan returns at the call of Caspian using Susan’s horn, a gift left behind from Father Christmas, bringing with them prior knowledge and fresh awareness of fulfilled prophecy and the reality of Aslan’s reign. They thus are devastated by what has befallen their countrymen—“Old Narnia” is to them the only Narnia they know.

It is contemporary Narnians who exhibit a diffidence and befuddlement that inhibits their ability to distinguish fact from falsehood. They must learn how to fathom such “confusion,” perplexity about where one is, anxiety about who one is, ignorance about national origins and personal destiny, and profound ambiguity about the stories we are told and the stories we tell ourselves, and what we should then believe. Does this not sound familiar in our world?

“Old truths don’t lose their value or validity because they are old.” This is an important maxim governing the whole of the Chronicles—but especially relevant here. One must not judge the validity and truth of a statement by “when” it first originated. This is a fictional treatment of the challenge of “chronological snobbery,” which Lewis faced and defeated, described in Surprised by Joy as a key to his own liberation.

Dr. Cornelius, Caspian, Trumpkin, Reepicheep, all must fight through their skepticism in order to accept as true the “old” belief that Aslan exists and Narnia’s future is dependent on this “ancient” knowledge. Life for us all is “in medias res,” in the middle of things; we don’t get to choose the moment in which we will enter the world, nor what conversations, ideas, victories, and defeats have preceded us, or will succeed us.

We have only the “now,” and we must piece together the puzzle of our lives moment by moment. To accomplish this —bravery alone does not suffice. Without a compass of faith, without a community of believers it is a daunting, maybe impossible task. New Narnia needs the Old Narnia. Both rest on the foundation of Aslan’s justice and the fellowship of those who embrace it.

Lucy’s Timely Lesson

Timing is everything. And Prince Caspian teaches us the time is always now. The most poignant lesson in this Narnian tale once again occurs off-stage, and in the interchange between Aslan and the ever-faithful and spiritually perceptive Lucy, who proved herself again to be the more watchful and discerning among her clan—sensing the presence of the invisible Aslan but unable to convince the others. Finally, the lion returns and she must leave camp at some risk to embrace him:

“Aslan,” said Lucy. “You’re bigger.”

“That is because you are older, little one,” answered he.

“Not because you are?”

“I am not. But every year you grow, you will find me bigger.”

Aslan’s stature grows in the estimation of Lucy because as she matures, the more she understands and is able to absorb. But while Lucy luxuriates in Aslan’s comforting presence, seeing him as even grander than before, she wrongly expects that, as before, he will roar off and solve everything for them—forgetting her stake in the mission, that it will take a royal team to press on to the rescue and restoration of Prince Caspian to the throne. Aslan must disabuse her of her pacificism. And disavow her complaints about the failing vision of her siblings.

For a time she was so happy that she did not want to speak. But Aslan spoke.

“Lucy,” he said, “we must not lie here for long. You have work in hand, and much time has been lost today.”

Lucy had given up and given in too soon. and now was explaining away her failure instead of rising up to the occasion. She persists in trying to rationalize her behavior by demanding to know how it might have turned out if she’d persevered sooner.

“You mean,” said Lucy rather faintly, “that it would have turned out all right—somehow? But how? Please Aslan! Am I not to know?”

“To know what would have happened, child?” said Aslan. “No. Nobody is ever told that.”

“Oh dear,” said Lucy.

“But anyone can find out what will happen,” said Aslan, “If you go back to the others now, and wake them up; and tell them you have seen me again; and that you must all get up at once and follow me—what will happen? There is only one way of finding out.”

Finding out what will happen by doing Aslan’s will is superior to idle speculation, for involves the investment of the individual in the outcome; “Things never happen the same way twice” in Narnia, and they never happen without the conscious and constant vigilance of the Good and the True to act on behalf of righteousness and justice.

Lucy and her kin rely on the lessons taught and character built during their earlier encounters with Aslan, carrying on the work of Aslan in his seeming absence. They must be rational without being rationalistic, trusting without been naïve, and courageous without being reckless. Lucy, with Edmund at her side this time, are both willing to see with their hearts—and readily respond to her vision of Aslan’s approach that has been beckoning them forward.

Their valor shows them and us that we can trust Aslan to be Who he is, yesterday, today, and forever; this really is the supreme fact of Prince Caspian. Reepicheep, the chivalrous mouse, who takes a more central role in The Voyage of the “Dawn Treader,” understands this, and proves that strength and courage are not measured by the stature of the individual but the size of his heart.

The Perils of Lost Perspective

In Prince Caspian we frankly confront the consequences of lost perspective, and worse, lost faith and trust among friends. Leadership is taking to heart and acting upon the lessons Caspian received at the feet of Doctor Cornelius, and these are essential to his kingly ascension. The stories of Old Narnia must be handed down, faithfully, generation to generation. Without them, Narnia ceases to exist—perhaps a lesson for our world as well? Caspian progresses throughout the tale in his understanding of how his father has been murdered and the personal risk required of him to confront evil head-on.

For Sons of Adam and Daughters of Eve it is not the shock of battle, but the comforting familiarity of old friends and the promise of new adventures in their company that emboldens them; their faith in Aslan is unshaken, though his timing may not be theirs. The treacherous King Miraz, family member but usurper of the throne, can finally trust no one, even his own advisors, who help engineer his death. By contrast, Narnia teaches us that good character somehow begets great friendships—and teaches us how to extend and nurture them. Not so for corrupt and conniving despots.

For those who know Lewis’s biography, these lessons of Prince Caspian provide an interesting and salutary link to the last several chapters of Lewis’s autobiography, Surprised by Joy. Here, Lewis explores the theme of confusion and clarity in terms of his own life, as Lewis weaves the threads of his past into a tapestry that helps to dispel his confusion and reveal his discoveries about heritage, faith, hope, and destiny. Like Caspian, Lewis must sort out truth from falsehood, friendship from mere companionship, and ultimate joy from temporary pleasure or comfort. He has to “read” his life story with the help of insightful peers and mentors in order to embrace his true self. While there was no one, single “Doctor Cornelius” in his life, he did have his Chesterton, MacDonald, Barfield and Tolkien to lead him “home.”

The dramatic climax of thid story is not, however, the suspicious victory over King Miraz in battle, but the discovery of the now King Caspian’s true lineage, that he, too, is a Son of Adam, else he could not be qualified to reign in Narnia. In one poignant moment that epitomizes the humility required of true leaders, Aslan asks the triumphant Caspian if he were now ready to become king; “I—I don’t think so, Sir. . . I am only a Kid.” To his surprise, Aslan replies, “If you had felt yourself sufficient, it would have been a proof that you were not.” Caspian needed to know the limitations of his own powers, and when he needed to rely on others—and especially Aslan—to win the day.

Nikabrik: The Dwarf Who Would Be Lost

As is the case with LWW, there is yet a betrayer in Narnia, for found in Prince Caspian is a parallel story to King Caspian’s glorious victory is the tragic story of Nikabrik, the stubbornly faithless dwarf. Of all the sad stories of bewitched and bewildered creatures in Narnia who become captive of evil, none is more mournful than the tale of Nikabrik.

This wayward dwarf, incapable of overcoming his profound distrust of the “old stories,” epitomizes a less cunning but equally desvasting aspect of evil’s lure akin to that of the White Witch. Nikabrik—like the band of self-seeking dwarves who fall by the wayside in The Last Battle—is world weary and full of skepticism. When asked if he believes in Aslan, he shrugs that he will believe in “anyone or anything” who will throw off the yoke of oppression under King Miraz; he is not discriminating: “Anyone or anything, Aslan or the White Witch, do you understand?”

Though rebuked by the more pious and respectful badger, Trufflehunter, Nikabrik still harbors his doubts and nurtures his cynicism. As events progress, the impatient and unschooled Nikabrik, rejecting out of hand the promise of help from ancient prophecies or the mobilization of Caspian’s friends, instead puts his trust in his companions, a hag and a werewolf, and plans to call upon the dark magic of the long dead White Witch:

“All said and done,” he muttered, “none of us knows truth about the ancient days of Narnia. . . . Aslan and the Kings go together. Either Aslan is dead, or he is not on our side. Or else something stronger than himself keeps him back. And if he did come—how do we know he’d be our friend? . . . . Any anyway, he was in Narnia only once that I ever heard of, and he didn’t stay long. You may drop Aslan out of the reckoning. I was thinking of someone else.

This is the voice of despair and alienation masquerading as the voice of reason. So distant is he from Narnia’s traditions, its history, its promise—and its relationship to its Creator and King, Aslan—Nikabrik can seriously contemplate “a power so much greater than Aslan’s,” which he defines as holding “Narnia spellbound for years and years, if the stories are true.” Falsehood has become truth, black has become white, destruction has become destiny.

This is Lewis’s cautionary tale to any civilization drunk on the wine of its own self-importance and ability to survive or thrive without historical perspective and relationship to God. This is “chronological snobbery” gone wild, a disposition not only to disbelieve the old stories, but to substitute an opposite meaning for the original.

In the end, Nikabrik confesses, “Yes,” said Nikabrik, “I mean the Witch…We want power: and we want a power that will be on our side. As for power, do not the stories say that the Witch defeated Aslan, and bound him, and killed on that very stone which is over there, just beyond the light?” When the Trufflehunter and others eloquently counter his virulent, militant unbelief, Nikabrik bellows:

“Yes they say . . . but you’ll notice that we hear precious little about anything he did afterwards. He just fades out of the story. How do you explain that, if he really came to life? Isn’t it much more likely that he didn’t, and that the stories say nothing more about him because there was nothing more to say? . . . . They say [the White Witch] ruled for a hundred years: a hundred years of winter. There’s power, if you like. There’s something practical. . . .Who ever heard of a witch that really died? You can always get them back.”

A witch who never dies, whose “practical” power to sustain winter a hundred years is more impressive than the return of the rightful king, the rallying of treasonous ne’er-do-wells to necromancy to revive her —these are the perverse foundation of the new society Nikabrik envisions for himself and fellow dwarves and outcasts. This is how bleak and self-destructive their own imaginations have become. But it cannot prevail so as long as there are those who love and trust the truth.

Night No Longer

In LWW, faithful Narnians faced perpetual winter; in Prince Caspian, they face remorseless revisionism—a rejection of their glorious heritage and a renunciation of the very foundation upon which their civilization stood.

The final trustworthy story of Narnia is to be written by the followers of Aslan: Dr. Cornelius, King Caspian, Reepicheep, the four Pevensies. That Grand Narrative must be told and retold with accuracy and attention to detail in the way Dr. Cornelius passed it on to Prince Caspian. It must be preserved, and most importantly, it must be lived.

For it is also our true story, which both retells and foretells our destiny. To divorce oneself from this history, from the true character of Aslan and real adventures of his loyal subjects, is to sentence oneself to disenchantment, self-doubt, and ultimate despair. In our times, more passive but still effective weapons of evil have arisen, an arsenal that is residual in every culture that becomes content to jettison its historical roots and to reinvent itself at will.

These include the big lie, the doctored report, the distorted original, the reversed interpretation, the deliberately forgotten premise, and, most deviously, the cultivation of a mistrust of history itself. The latter sentiment, put bluntly, means “if you can’t change history, then ignore it—or make up your own.”

Caspian joins Narnian heroes, Puddleglum, Jill, Polly, Digory, Rilian, Tirian, Jewel, other of Lewis’s valiant characters, who testify to the need to resist these propagandistic tactics as actively as we in our times also resist sheer violence and physical intimidation to rob us our birthright of freedom and hope.

As you continue your own journey back to Narnia we hope Aslan grows bigger and bigger, and your heart continues to fill with wonder, and true valor.

(Copyright 2015 by Bruce L. Edwards. Click here for Permissions information)

I really enjoyed this blog post. I read often, but I don’t believe I’ve ever commented. I’m a university student at Oral Roberts. I became an avid reader of Lewis as soon as I started college. I started reading Chesterton, McDonald, and Lewis for fun and haven’t stopped since.

I believe in an earlier post, you said the movie makers of Prince Caspian themselves “spent no time in Narnia” or something to that effect.

I agree.

I don’t have much else to say. I do, however, want to thank you for keeping this blog. It’s a joy to read. I’ll try to remember to leave comments more often.

Blessings,

Courtney F

Comment by Courtney F — 21 May 2008 @ 12:41 PM

Thanks, Courtney! I am very grateful for your observations. Comment often! — Bruce

Comment by Bruce — 21 May 2008 @ 1:33 PM

With all the commentary circulating about the movie right now, I really enjoyed this post.

In response to your opening paragraph, Prince Caspian actually is one of my favorite Narnia books (along with LWW and Voyage of the Dawn Treader). I think it may be because of the scene you quoted with Aslan and Lucy; this is probably my favorite passage in all of the books.

As you mentioned, the character of Nikabrik, and all of the themes Lewis deals with through that character, make this volume every bit as weighty as the others. I also love seeing the contrast in Edmund’s character from LWW–his nobility in general, and his willingness to believe Lucy and follow Aslan.

Thanks for the post!

Comment by Danielle — 21 May 2008 @ 4:33 PM

Thanks, Danielle. Always good to know there are committed readers out there who see the worth and depth of Lewis’s “flawed” works 😉

Comment by Bruce — 21 May 2008 @ 4:49 PM