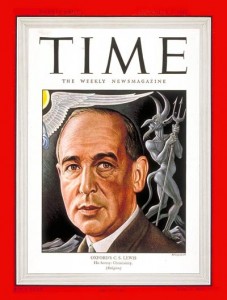

How to Honor C. S. Lewis on His 116th Birthday

December 4th, 2014 | Skip to comments

by Dr. Bruce L. Edwards

If C. S. Lewis were present today, where I live in Willow, AK, he would be celebrating his 116th birthday, and probably would be up for a brisk walk on this Arctic tundra that is home to many of his readers and admirers, even in this village of less than 2000—as long as it ended in a pub with a roaring fire.

The fact is, it’s hard to travel anywhere on the globe these days that doesn’t have a library or a bookstore featuring Jack’s learned, inspiring volumes, even here in Alaska.

The fact is, it’s hard to travel anywhere on the globe these days that doesn’t have a library or a bookstore featuring Jack’s learned, inspiring volumes, even here in Alaska.

But why should I say, “even in Alaska”? There are as many seekers in this polar landscape, in percentage, if not volume, as there are anywhere else in the world’s metropoli. I have met few people whose lives Lewis has touched who aren’t living lives of quiet definition, men, women, and children who seem, like Archimedes, to have found a place to stand (using the lever, or fulcrum Lewis has provided), and are moving the world (traversing a level, navigable surface) illuminated by Lewis’s uncommon understanding.

I myself have written many a tribute to Clive Staples Lewis over the nearly 45 years I have been reading him, listening to his wisdom, treasuring his inimitable imagination, mesmerized by the full scope of the skill and persuasiveness of his rhetoric, forever grateful for his insights into the faith proclaimed once for all by the apostles and a heavenly revelation ultimately embodied in the person of Jesus, our once and future returning King, whom Lewis knew and trusted intimately. Yes, all of that. Again and again.

But before I am further tempted to repeat things I’ve said before, let me attempt to deepen our debt to Lewis in a different way by moving to a fresh subject on his 116th birthday: how we can best honor the continuing memory, and the ongoing ministry, of Lewis-–almost exactly 51 years after his death (November 22, 1963)?

Too often I notice, we are asking, in effect, the wrong question: “What else can Lewis do for us?” What knotty problem of the 21st Century can he contextualize and help clarify for us what we should do or what we should believe? What clever quotation of his can I unearth next to sprinkle about to settle big issues and make my social media credos appear more profound than they actually are?

We want him to be a prophet of a different kind than he was; instead of relishing his ability to warn, to instruct, to prepare, to edify, to delight, to instill character and virtue, directing us to Scripture, we prefer something else, something reducible to an amiable carnival mentalist, a feckless Nostradamus who can render (byte)-sized predictions, or a prescient Wall Street analyst who will spot trends and helpfully encapsulate the directions society will be taking next so we can profit by them.

Curiously, we expect Lewis to help us be ahead of the game, when he decidedly preferred to stay behind it. There is no more determined or unrepentant anachronist than Lewis, one who urged us to look back before we could be possibly be ready to look forward, to read one “old book” for every modern one we may errantly pick up.

No, this isn’t the Lewis we meet in his own voice in his own words; he’s offering no horoscope to us—except by the rough, disdainful appropriation of his genial personality by would be admirers who betray Lewis’s formidable erudition in exchange for glib soothsaying. His sheer quotability is our enemy, our siren song his eminent excerptability, if we choose to ignore what leads up to and past it in his prose.

If not this kind of hero worship and shallow veneration of his one-liners, then what might we do best in honoring Lewis in his 116th year? For starters: here’s are several curmudgeonly suggestions for your consideration.

- Fewer books, please.

The proliferation of books about Lewis, the atomization of topic and focus within them, and the subsequent adulation of said authorship accruing to their specialization–a parallel phenomenon one might sat to the explosion in craft microbrewery experimentation–helps to diminish Lewis, not enlarge him. I thought we had reached the zenith of such exploration long ago, in the late 1980s, perhaps. But, to “the making of many books [about Lewis and the Inklings],” there is no end. - Read Lewis exhaustively before putting cursor to screen, if at all.

I admit to being astounded by the sheer number of essays, blogs, reviews, and conference (junkets) that feature, forgive me, “amateur” (i.e., hands-up, self-proclaimed, unjuried) scholars of Lewis, whose work reveals they have read only a handful of his (most popular) works, but feel confident enough to proclaim a new or more ingenious vantage point from which to assess the value or meaning of Lewis’s lifetime legacy.I reckon that I read about 40-50 Lewis-related manuscripts a year on behalf of publishers and journals seeking guidance, and I regret to say that the insights that emerge from them on the subjects they are tackling are few and far between; their flaws emerge chiefly from one main source: they haven’t read Lewis widely and deeply. They write without the acquaintance of or the facility with the multi-genre perspicacity that characterizes and informs everything Lewis wrote. Poet, literary critic, historian, linguist, fantasist, mythologist, philosopher, hermeneuticist, apologist, theologian, homiletician, memoirist, correspondent, anthologist, translator: these experiential roles and tasks, and many more, name significant vocations Lewis mastered and practiced with great skill and historical understanding.

Isolate even one or two of these “identities” from the rest, ignoring their essential global contribution to the uncompartmentalized Lewis, and you have significantly injured your ability to speak with any authority or insight into his fictive worlds or non-fictional prose.It is alarming to note the number of published authors (including some recent biographers) on Lewis who do not seem to have read or, if they have, fathomed, such integral-to-understanding-Lewis works like An Experiment in Criticism, English Literature in the 16th Century, The Allegory of Love, Preface to Paradise Lost, or his innumerable essays and personal letters on education, literacy, 20th-Century theology, literary theory, and psychology.

Over the past ten years, save books and essays written by authors named Glyer, Root, King, Downing, or Ward, those publications that have seen the light of day tend to reflect a very narrow and narrowing perspective, usually predicated on the author’s subject matter specialty, rather than a deep submersion in the totality of Lewis’s life and work. The most important qualifying preparation for writing credibly about Lewis is wide knowledge of his own subjects and the genres in which he wrote—and how he wrote strategically about the matters he cared most deeply about.

Nothing short of this commitment will yield the kind of authentic and incisive scholarship that illuminates rather than obscures or unwittingly misleads those who would most desire to understand and appreciate Lewis better.

- If you’re going to quote or excerpt Lewis, do it right.

The indiscriminate lack of accountability and absence of reliable systems of verifiability within the internet breeds a progressive inaccuracy of Lewis quotations and the growing emergence of a “people’s C. S. Lewis.” By the latter, I mean the attribution to Lewis all kinds of popular, colloquially awkward, and essentially unworthy sentiments—often enshrined in an ornate or artistic rendering of the quotation that speeds across social media unchecked. “As long as a tame lion is depicted,” I say, disapprovingly to myself.Those most familiar with Lewis’s thought and characteristic ways of expressing himself acutely experience a jarring effect when they encounter a false attribution or an inaccurate citation of something he supposedly said. Lewis is, indeed, aphoristic, inspiring many more readers and admirers to want to cite and spread his unique and memorable point of view than actually have a clear sense about what is and isn’t Lewisian.

This is, in the internet age, a tendency ultimately sure to be a reductive practice, one that minimizes and dilutes Lewis’s impact, especially to consumers all too accustomed to the sound-bite that restricts rather expands access to the larger, even more compelling ideas to which it is intended to point. Simply put: recommending a pseudo-Lewis quote will undermine your credibility, and certainly that of Lewis himself.

Today’s diminished attention spans and the accompanying premature, illogical conclusions drawn from counterfeit Lewiston passages may eventually distract readers away from, rather than toward, a writer like Lewis, who wishes to invite his readers for a complete meal, not just an appetizer. If one simply must irresistibly employ a Lewis quotation (I do know the feeling), try to follow these simple rules:

(a) Don’t obtain your wording (or citation) from an internet source; go to your own bookshelf and quote Lewis verbatim from the original book, chapter, and page, and list the full source in your message.

(b) If you don’t own a book personally that is purported to be the source from Lewis, you can at least attempt to do an Amazon (“Look Inside”) or Google search that contains a suitable annotation that indicates original source materials. Note: I still advise against this third-hand attribution.

(c) A tell-tale sign of a fake Lewis quote is its use of any contemporary term or event that Lewis is unlikely to have been familiar with, or be unlikely would use because it obscures its message, for Lewis will always be clear, use vivid metaphors, and provide a memorable phrasing. This is especially true of trite Americanisms or typical, uninspired “bumpersticker” prose that is unworthy of Lewis’s usual eloquence and elegance (e.g., his use of rhetorical parallelism or rejection of needless hyperbole). Likewise, beware any brutally, breezy surface, modern attitude expressed toward anything [love, commitment, honor, faith, child-rearing, etc.] on which Lewis has written some extended and deeply profound things (The Four Loves, e.g.). If it sounds like Dr. Spock (or Dr. Seuss or Leonard Nimoy) it is likely to be a false attribution.

(d) If you just have to quote, then use more than one line, and choose a rather healthy excerpt to indicate the larger gist of what Lewis is trying to convey. A good guide to excerpting well is found in how Lewis himself treated his beloved mentor, George MacDonald, in his little book, George Macdonald: An Anthology (Macmillan, 1947). - Lewis’s autobiography belongs to him; don’t presume to surpass it or usurp his historical moment..

Some recent well-meaning scholarship has encouraged our suspicious about the effectiveness of Lewis’s memory in recalling or recording past personal events, especially in his autobiography, Surprised by Joy. Lewis, so it is said, was not good at recalling exact dates and may have misremembered, e.g., the date of his “conversion.” Fine and good. (In the interests of full disclosure, let me specify that I may not be able to recall the precise date of my own conversion, that there may be have been several, and my present inability to pinpoint which one God “counts” may not be settled until eternity descends. If pressed, I will designate October 19, 1970.) There could be several reasons for Lewis’s use of the “zoo and sidecar narrative,” and it’s been amply speculated upon.However, it seems to me some commentators may have inadvertently cast some general aspersions on Lewis’s active memory, period. “Perhaps he is not reliable on this or that, either” it is said, with supposed momentous consequences, stirring visions of the ever more devastating “post hoc ergo propter hoc” fallacy. But most accounts, i.e., from the contemporary testimony of students and close friends, Lewis had a prodigious memory, especially in his ability to cite in their entirety (and by page number in the volumes which the are found) long passages from literature. This does not strike me as a stunt of Lewis, nor an apocryphal tale trumpeted by gracious admirers. But it is just this gotcha phenomenon that irks and disquiets.

What is it that, again I will use the term, “amateur Lewis scholars” wish to accomplish by deployment of this meme (and a related one: “he was hopeless in maths, unlike his mother, Florence,” champion of Queens University Belfast?) To open up a crack in Lewis’s vaunted armor of infallibility? Who “vaunted” that, anyway? (See #5 below.) Not Lewis. To create some space for extra-special spelunking in the life circumstances and chronology of Lewis’s biography? Well, he, and Barfield, and Minto, and Albert, are long dead—have at it. But, in the end, unless some kind of family deceit or professional subterfuge is alleged, this all seems to be, much ado about, well you know.

It’s not that we should not strive to be accurate, precise, and detailed—restive until we firmly validate what we can know about history, not the least of which that involving Lewis. But I am not always convinced that is really what is at stake: accuracy. Rather, it sometimes seems like what is under consideration is territory. New dubious territory. The expanding writeaboutabiity of topics within the Lewis canon, the “still-more-than-you-know-that-there-is-to-know syndrome that is characteristic of the 21st Century internet Reddit culture, in which, as we say (and Lewis eloquently denied) that everyone is entitled to “our own facts.”

Lewis’s letters and memoirs (Surprised by Joy; A Grief Observed; aspects of The Pilgrim’s Regress), the Lewis family papers, Warnie’s diary, first-person accounts of his contemporaries, including that of Joy Davidian Gresham, these are still to me the most accessibly credible and compelling accounts of the person we know as Clive Staples Lewis, and the only records I feel comfortable recommended to anyone who wishes to know who the “real” C. S. Lewis is.

Each biography and biographer ultimately picks and chooses, has a narrative operating in his or her mind that construes, constraints, or, as it happens, ignores the facts according to the life perceived, life preferred. Recent biographers (of the 50th anniverary variety) do seem to me to be awfully heavy on tree analysis and woefully short of spotting the forest. The microscope must yield to, or at least include in equilibrium, the macroscope in future biographical endeavor.

Until then, the most disconcerting statement overheard by someone who loves Jack will continue to be, “Yes, as a matter of fact, I am writing a book about C. S. Lewis.”

- Emulate Lewis in his practice of faith, but don’t try to out-Lewis Lewis. You will be embarrassed. .

I am surprised and considerably dismayed by the variety and number of current commentators on Lewis who, unprompted, feel compelled to speak at all, but then start by pointing out the obligatory “Lewis was a flawed man with this or that foible or error or outright heresy. . .”As if this presumptive declaration confers upon one license to then decry Lewis’s indefatigable popularity, followed by establishing one’s own superiority by a series of distinctions without a difference. This diatribe shows up in all manner of theological contexts, among professional literary historians and critics, down the hallways of philosophy departments, and, of course, within the study of “the Inklings.”

To wit: “Lewis lacked theological integrity or he would have completed the journey home to Rome.” “Lewis evinced a liberal stance on the Bible and failed to understand the doctrine of inerrancy.” “Lewis’s Narnia tales are thin, inconsistent. evangelistic tracts compared to the rich and complex mythopoeia of Tolkien’s middle-earth, whose stories will be read when Lewis is long forgotten.” “Lewis espoused an unmistakable misogyny in his fiction and in his cultural commentary.”

Now any or all of these judgments may be valid to one degree or another, depending on vantage point, historical context, or motive. (The pretext of not having “motive” is itself a kind of motive.) One version of these charges may indeed provide enough leverage to enable one to dismiss Lewis from the human race. But one thing that will never do is to undermine his example of an earnest Christian trying to “work out his own salvation in fear and trembling.” It is frankly unassailable.

Lewis’s notable generosity with personal funds, his dedicated confession of sins, his mercy-compassion driven prayer life, his noble and compelling defense of the rationality of faith and his championing of the historicity of the person of Christ and his resurrection—these, among many other qualities and exuberances of his life post-conversion, mark him as a serious, devout, and utterly converted believer.

Despite flaws real or imagined, C. S. Lewis continues to flourish as an exemplar of mere Christianity well into his second century of influence because of the genuineness of his supernaturalist, trinitarian faith that even as ardent an atheist as the late Christopher Hitchens recognized,

“[Lewis] deserves some credit for accepting the logic and morality of what he has just stated. To those who argue that Jesus may have been a great moral teacher without being divine (of whom the deist Thomas Jefferson incidentally claimed to be one) Lewis has this stinging riposte: ‘That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic—on a level with the man who says he is a poached egg—or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God: or else a madman or something worse. You can shut Him up for a fool, you can spit at Him and kill Him as a demon; or you can fall at His feet and call Him Lord and God. But let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about His being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.’ [. . .] I do credit [Lewis] with honesty and with some courage.”

The fact is, non-foundationalist Christian philosophers in our time tend to enjoy, or at least, do not fret, pointing out that this trilemma is “not an effective argument,” and maybe not even be an “argument” at all.

But they miss the point. Lewis may or may not be trying to convince someone with this declaration, but he certainly is trying to accomplish something else: offering a poignant analogy of what acceptance of the lordship of Jesus Christ entails, that which Lewis himself was willing to embrace and earnestly offer to others as the core Christian belief.

Lewis doesn’t just talk a good creed, he lives by it—and he dies for it, and will remain worthy of our respect and admiration as long as there remain groups of believers meeting to exhort and admonish one another toward “love and good works. . .” (Hebrews 10:24).

One could have hardly foreseen what would happen after the last generation of readers who actually knew Lewis or Barfield or Tolkien, or even knew their works firsthand—which has meant a deep descent into trivia. A moratorium on monographs would do Lewis a great service, and put a halt to a rampant reductiveness that epitomizes the opposite of how he read and how he engaged others about what he read—and recommended.

The steady voluminous expansion of secondary sources foregrounding their excruciating minutia of footnotes has had the debilitating effect of pushing Lewis’s own primary work onto tertiary places on library and bookstore shelves, and in readers’ hearts and minds. Amend Lewis’s wisecrack, “Odd, the way the less the Bible is read, the more it is translated,” to the inevitably strange observation, “Odd, the way the less Lewis is read, the more books are written about him.”

Finally, the main way I am going to honor Lewis on his birthday is to reread respectfully, expectantly, and attentively, his last published work, Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer.

Finally, the main way I am going to honor Lewis on his birthday is to reread respectfully, expectantly, and attentively, his last published work, Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer.

And I recommend to you that you select a book of Lewis’s most poignant and full of impact for you—as Letters to Malcolm represents to me his mature, valedictory, ultimately hopeful and endearing thinking about the Christian faith, his end, and our own, as we see the day drawing nigh. Selah.

[…] Click here to read the whole post. […]

Pingback by How to Honor C. S. Lewis on His 116th Birthday | Mere Lewis — 20 December 2014 @ 7:19 AM