Happy Birthday, Clive! 112 Years Young!

November 29th, 2008 | Skip to comments

My annual birthday tribute to Jack.

My annual birthday tribute to Jack.

(November 29, 1898-November 22, 1963)

Dr. Bruce L. Edwards

Professor of English and Africana Studies

Bowling Green State University

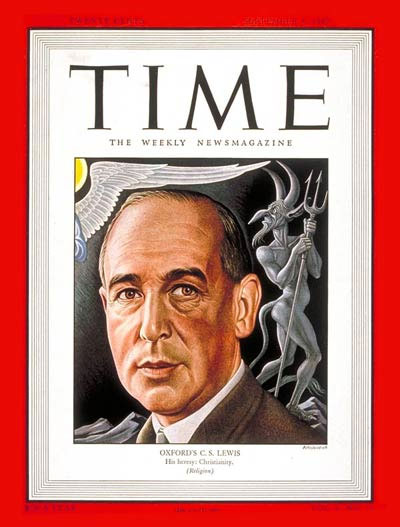

Renowned author and critic C. S. “Jack” Lewis was born in Belfast, Northern Ireland 112 years ago today.

Renowned author and critic C. S. “Jack” Lewis was born in Belfast, Northern Ireland 112 years ago today.

Lewis, who died auspiciously on the day President Kennedy was shot in Dallas, November 22, 1963, will be remembered by some as a distinguished Oxford and Cambridge literary historian, especially notable for inaugurating rather than climaxing his scholarly career with a magnum opus.

This work, The Allegory of Love (1936), established Lewis as a formidable critical talent whose scholarship on medieval and renaissance literature would set the standards and the terms of debate in scholarly circles on both sides of the Atlantic for decades to come. And in numerous publications over the next 25 years, Lewis would prove himself to be both prolific and profound in his understanding of the literary foundations of Western civilization.

But it is not this “scholarly Lewis” whose life and work will be primarily commemorated this weekend, estimable though his academic achievements may be. Rather it is the “other Lewis”-the risk-taking writer of supernaturalist science-fiction and fantasy, the winsome Chronicler of Narnia, and the last century’s most popular and influential Christian apologist—whom the vast majority of his readers adore, and whose religious canon and eventful spiritual biography will be given honor.

Lewis is memorialized first and foremost for his vocation as a orthodox Christian apologist in a time of militant irreligion and preferred New Age mysticism, and this is one of literary history’s great ironies.

And it is a story worth exploring, especially in view of Lewis’s recent notoriety stemming from the 1993 movie Shadowlands, which featured Anthony Hopkins as the venerable scholar in the “true story” of his improbable romance with New York poet and Jewish convert to Christianity, Joy Davidman Gresham, played by Debra Winger.

Many Lewis admirers found director Sir Richard Attenborough’s Lewis an unrecognizable distortion and his relationship with Joy Gresham overly compressed and inexplicably absent of the spiritual fervor which brought them together.

Who was the real C. S. Lewis and why should we remember him?

A bitter and confirmed atheist after his mother’s death when he was nine, a WWI veteran who while in the trenches of France jotted a poem decrying the “ancient hope” of a “just God that cares for earthly pain” as merely a “dream,” a self-described “prig” prepared to enter into postwar Oxford society as one more pretentious don promoting a lifestyle without inhibitions, Lewis is among the more unlikely converts among the literati of his time.

In his superb spiritual autobiography, Surprised by Joy (1956), Lewis recounts the circumstances that eventually led to his coming to faith: here are no Damascus Road dramas, but instead a series of ruminations about crucial books and providential friendships which led him out of unbelief onto a principled agnosticism, and from there to a benign theism and, eventually, to orthodox, trinitarian Christianity.

Before his return to faith, Lewis would experiment with various “Northern” mythologies, explore the world of the occult, sample Eastern mysticism, and embrace philosophical idealism-all stopping points on his way to accepting the concept of a compassionate, incarnate deity proclaimed by Christianity.

The steady ascension of his mind and heart–both his reason and imagination–toward the renewal of his pre-adolescent faith is depicted by Lewis as the propitious encounter with two religious authors, and three key individuals, each of whom Lewis cites as a critical influence animating these gradual changes.

The first of these was George MacDonald, the nineteenth-century Scot Presbyterian minister and novelist, whose works, Phantastes and Lillith, Lewis read at age nineteen; these, Lewis declared, had “baptized” his imagination, preparing him for a preternatural world beyond the strictly materialist one he had grown so tired of.

Another author of influence was G. K. Chesterton, popular and London journalist and sprightly Christian apologist in his own right. His work, The Everlasting Man, a portrait of Christ and of his impact on culture, presented Lewis with a “Christian theory of history.”

(Lewis could thus say: “In reading Chesterton, as in reading MacDonald, I did not know what I was letting myself in for. A young man who wishes to remain a sound Atheist cannot be too careful of his reading. . . . God is, if I may say it, very unscrupulous.”)

Apart from his voluminous reading–and Lewis may reign as the original “multiculturalist” for the inclusive and perspicacious scope of his reading–three persons stand out as particular provocateurs, the first being the “Great Knock,” William Kirkpatrick, Lewis’s tutor before entering Oxford.

“Kirk,” as Lewis called him, taught Lewis a form of rigorous inquiry that sought objective truth through the relentless probing of an opponent’s positions and definitions, a fierce and, in Kirkpatrick’s hands, exaggerated version of Socratic dialogue. (It is clear that the Professor Digory Kirke of the Narnian tales is intended as a tribute to Lewis’s beloved mentor.)

No less important to Lewis was his encounter and subsequent friendship with Owen Barfield, whom he met at Oxford in 1916. A keen dialectician himself, Barfield’s chief contribution to Lewis’s journey of faith, was his demolishing of Lewis’s “chronological snobbery,” the “uncritical acceptance of the intellectual climate common to our age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that count discredited.”

Liberated from the notion that the past was invariably wrong and that the present always the barometer of truth, Lewis was able to embrace the possibility that the ancient Christian narrative could have validity even in the twentieth century.

The final “blow” against Lewis’ youthful atheism came in his frequent companionship with devout Catholic, J. R. R. Tolkien, himself later to become extremely popular as the creator of Middle Earth, author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

It was Tolkien who led Lewis to the conclusion that while Christianity may itself comprise a mythology of sorts–it is, in fact, “the true myth, myth become fact” and the one in which Lewis could put his full confidence, heart, mind, and soul.

The post-conversion Lewis, circa 1931, began thus a dual career: on the one hand maintaining his scholarly poise and productivity, astonishing colleagues with both his erudition and his prolific publication rate; and, on the other hand, slowly and quietly building a reputation as a modern day Aquinas or Newman, a “translator” and “popularizer” of Christian doctrine for a skeptical and credulous age.

After creating the first of what would become a trilogy of “interplanetary romances,” Out of the Silent Planet (1938), using the genre of science fiction to “steal past watchful dragons” to promulgate his Christian views, Lewis published his first purely apologetical work in 1941, The Problem of Pain.

This book, which tries to reconcile the concept of an all-powerful and good god with the presence of evil and suffering in the universe he created, drew the attention of James Welch, head of Religious Broadcasting for the BBC, who would inadvertently launch Lewis on the road to becoming a religious celebrity.

Welch was so impressed with Lewis’ compelling argumentation and fresh analogies in explaining the essentials of the Christian faith, he persuaded Lewis to commit to a series of radio broadcasts that would commence late in the summer of 1941.

Lewis made his debut at 7:45 PM, Wednesday, August 6, 1941. Later in the evening, air raid sirens will blare all over Britain, preparing citizens for what may be yet another bombing attack from Germany.

That night a most unlikely new radio personality was to be born, speaking on the topic: “Right and Wrong as a Clue to the Meaning of the Universe.” Lewis, with no particular experience in broadcasting nor in speaking to such a diverse, indiscriminate audience, was called upon to rally a fearful nation beset by war to courage and to hope.

Lewis was such an immediate sensation–hundreds of letters, pro and con, pouring in from all quarters of the United Kingdom–the BBC invited Lewis to extend his original commitment first to eight, then to twelve, and, finally, to twenty-six broadcasts over two years.

These talks became the foundation for the book eventually published as Mere Christianity (1952), the most widely read (and purchased) work of Christian apologetics of the last fifty years—and now available all over the world “rediscovered” by the Chinese, the Koreans, the Indians, and a whole host of other people groups.

It is a volume that continues to be credited for countless conversions and “re-conversions” by the likes of such disparate people as Nixon “hatchet man,” Charles Colson and former Domino Pizza magnate, Tom Monaghan.

Lewis’s reputation as a witty, articulate proponent of Christianity continued with The Screwtape Letters (1942), an “interception” of a senior devil’s correspondence with a junior devil fighting with “the Enemy,” Christ, over the soul of an unsuspecting believer.

Lewis’s most notable critically and commercially successful set of Christian texts, however, is certainly his seven-volume Chronicles of Narnia, which he published in single volumes from 1950-56. These popular children’s fantasies began with the 1950 volume, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, a tale centered around Aslan the mighty lion, a Christ-figure who creates and rules the land of Narnia, populated by talking beasts and featuring the improbable adventures of four undaunted British schoolchildren who stumble into Narnia through a clothes closet.

In canvassing his public career, it is thus no exaggeration to say that C. S. Lewis–“Jack” to his friends and family–is the most widely read Christian apologist of the 20th and now the 21st Century, his works devoured by evangelicals, mainstream Protestants, devout Catholics, and Orthodox believers alike. And many non-Christians.

His Chronicles of Narnia sell in the millions annually, the movies creating more and more readers, and all of Lewis’ works, included the more obscure, early literary critical works, remain in print–perhaps the true measure of his continuing impact.

How is one to explain this phenomenon?

For one thing, the dour, retiring Lewis depicted in Shadowlands, inexperienced with women and children, perpetually solemn and given to excessive brooding about suffering and God’s penchant for using pain to “rouse a deaf world” to action, could never have attracted the following the real Lewis has, let alone the attention of as vivacious and intellectually potent a woman as Joy Davidman Gresham.

According to the Attenborough script, Lewis met Joy–and finally his life blossomed. Embracing her exuberance and American brusquery, Lewis comes out of his shell, suppresses his doubts, inherits a family, and enters into an idyllic though short-lived marriage stopped cold by Joy’s bout with and eventual death from bone cancer.

At the end of Shadowlands, Lewis is seen skulking about, grasping for straws of faith, questioning the existence of heaven, and rebuking those who remind him of his former Christian confidence. True to life? Hardly.

As one who has spent the greater part of his professional career studying the life, works, and times of Lewis, and who has been serving as the head advisor to a documentary project on Lewis in production for PBS, I can say, unequivocally, the Lewis of Shadowlands–even conceding generous poetic license–never existed.

The “historical” C. S. Lewis known to friends, students, colleagues, publishers, and correspondents–and as revealed in his own works–was a gregarious, ebullient, even impish sort of fellow who loved talk, conversation, “performing”; he was, in his day, the most popular lecturer in Oxford, one whose presentations were always standing room only.

Jack loved to meet with friends Charles Williams, J. R. R. Tolkien, Owen Barfield–a group labeled quaintly “the Inklings”– at a favorite local pub to read aloud from their works in progress, downing a Guinness or two or more along the way and entertaining anyone who strayed in their path.

Far from being an austere or humorless conservative, Lewis practiced and affirmed a robust, cheerful, and decidedly intellectual brand of Christianity informed by his own encyclopedic reading of time and culture and filtered through his Irish literary upbringing.

The Lewis who eventually does meet Joy Davidman Gresham in 1952 has behind him two years of intimate correspondence with her, the knowledge that she has great familiarity with his own story and theology, and a profound respect for her own creativity and scholarly prowess.

While there is no question that Joy’s sudden presence in his life in some sense “revives” Jack’s literary career, the personal transformation he experiences is much more subtle than that Shadowlands depicts.

It is one more accurately seen as quiet renewal more than as radical shift in temperament; by all accounts, some of them begrudging, the couple made a formidable duo, soulmates at last together, united by faith, hope, and love.

The movie does well cover the cruelty of their relationship’s brevity: Joy is diagnosed with cancer, rallies, and then succumbs. Jack takes Joy’s death hard–as would any husband. He wrestles openly with God–admirably and candidly told in his own memoir, A Grief Observed–explores his loss, but then returns, chastened yet emboldened, to his faith.

Who was the real Lewis and why does he remain so influential?

Owen Barfield’s description is apt: “Somehow what Lewis thought about everything was secretly present in what he said about anything.” Lewis’s life was, in other words, thoroughly integrated; a man whose presuppositions about life, faith, and reality, his reason and imagination, were all surrendered to God, this spiritual integration manifested itself in all that he wrote or said.

But there is more to it than even this. As a witness to the remorselessly sectarian violence of his native Belfast, Lewis came to care most about what he called “mere Christianity,” that is, the essentials of the faith, that which has been the center of the creeds of the church since the apostles announced it.

It was the gospel freed of denominational idiosyncrasies, the debris of history, and focused on the essential truth of the identity and mission of Jesus of Nazareth. This “mere Christianity” focused not on what divides but on what unites Christians.

It is this Lewis that millions of Christians–and nonChristians alike–celebrate during his birthday.

By all accounts, Lewis was a generous, self-effacing person who gave tirelessly of his time and money to the needy and an indefatigable correspondent to the spiritually curious or wayward; he was also a man devoted to a fault to his students and friends.

Whatever else Lewis was, he was a man of faith willing to pay the price for his public defense of Christianity; deplored by colleagues jealous of his scholarly prowess, shamed by his open association with “popular literature,” and embarrassed by his public defense of Christianity, Lewis was denied a professorship at Oxford at the peak of his literary scholarship.

As Christopher Derrick, a former pupil and longtime friend of Lewis, has judiciously observed, Lewis was a man willing to “challenge the entrenched priesthood of the intelligentsia.” In short, one finds in Lewis an uncommonly sober and articulate skeptic of the modern era, one forthrightly opposed to the “chronological snobbery” of our times that assumes truth is a function of the calendar and that the latest word must be the truest one.

Were I to describe Lewis in a phrase, it would be this: Lewis is a man who knew he lived his life before Pilate. That is to say, I believe Lewis carried out his daily tasks as teacher, citizen, believer as one who knew he was always before a skeptical audience like the New Testament’s Roman interrogator of Jesus, an audience —in or out of the church—that too often masks its fear of knowing the truth behind indifference, or the pretense of being “on the search.”

Such a writer will seem most original and most courageous in a time of doctrinaire relativism and starry-eyed post-postmodernism. While Lewis caricatured himself as a dinosaur, the “last of the Old Western Men,” many celebrating his heritage today would see him instead as a forerunner of what may still be the ascension of principled men and women of faith in an age that derides the pursuit of truth and mocks the desire to see virtue honored.

Thus, one of the greatest things Lewis has to teach us as we inhabit a new millennium is this credo: To know the truth I need not be part of an elite or intelligentsia, I need only to be human: I am human, made in the image of God, and therefore I may know the truth.

Access to truth, to the real world, as opposed to the shadows, is the birthright of all. To resist this dilemma, we must follow Lewis in refusing to divorce our personal faith from our public behavior. We must live the faith in and out of our cloisters. We must not retreat from the public square.

While the privatization of faith is something that Lewis, perhaps the 20th-century’s century’s greatest convert from unbelief, would find it both antithetical to true faith, one doubts that he would cower or cringe at our new century’s challenges to Biblical orthodoxy. Rather, Lewis would see opportunity –opportunity for Christians to serve, as he put it, as both “specimens,” and as antidotes to chaos, that these times provide.

If we agree that Lewis’ life and career exemplify the virtue of rejecting the split between the sacred and the secular, the public and the private that haunts and inhibits so many of us, we can then find courage in sharing his obedience to St. Paul’s admonition to “be not conformed to this age, but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind” (Romans 12:1, 2). Lewis’s legacy points his listeners and his readers, his students and his friends, to a stance that integrates faith and life, vocation and confession.

Such a legacy would certainly surprise but gratify this great man of God. Selah.

Bruce,

Thanks for this tribute. Jack has been gone 45 years and keeps speaking to each following generation! May God grant us the wit and the conviction to do in our day and in our circles what he did in his.

Comment by Berke Larrimore — 29 November 2008 @ 8:09 AM